Why is the coat of arms awarded to 'George Gynn' similar to the arms of 'Gyney' of Norfolk?

The bearing of arms is just that. In ancient times, a 'Coat of Arms' representated someone who bears arms, in the literal sense, to fight in battle for the King, or Earl or Baron who is the authoritative leader of the person carrying the arms. Coats of arms identify the individual to whom they have been awarded both for supporters and fellow combatants. They also identify the person to their enemies. The bearing of arms is a serious matter implying a relationship of support and commitment to the country or place where the person lives. Back in the day, when military forces were actually mustered from local people under the 'Coat of Arms' of a Knight or Baron, shirking the responsibility it represents was considered an abrogation of duty and had serious consequences, just as how desertion is viewed today.

Depiction of a late medieval knightly tournament from King René's Tournament Book (1460s). The two teams stand ready, each side has 24 knights, all with heraldic surcoats and caparisons, and each accompanied by a banner-bearer with a heraldic flag. There is a central spectators' box for the four judges, where the heraldic shields of the competitors are displayed, the two teams being led by the dukes of Brittany and Bourbon, respectively, and one spectator box on each side for the ladies; inscribed over the boxes is plus est en vous, the heraldic motto of the Gruuthuse family of Bruges, attributed to tournament between Jean III de Gruuthuse and Jean de Ghistelles held in 1393.[1] The two dukes can be seen facing each other in the center of the front lines, each with a personal heraldic flag as well with a larger flag of the same design representing their team. The chief herald is also on horseback, between the two teams, wearing his own heraldic colours. Turnierbuch des René von Anjou, Paris, Bibliothèque nationale, Ms. fr. 2693; late 15th century (History of heraldry, Wikipedia)

The 'Duc de Bretaigne' on horseback, in full tournament dress.

René I d'Anjou, Traité de la forme et devis comme on peut faire les tournois, 15th Century.

(source: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b8449033b/f76.item.zoom)

At the same time, a coat of arms is awarded by a 'herald' who is the authority issuing the coat. In Canada, this authority is the 'Canadian Heraldic Authority', an office of the Governor-General. In England, it is 'The College of Arms', the successor to the 'Court of Chivalry' which in turn was the successor of heralds from ancient times. These are literally the only authorities that are enabled to issue coats of arms. Most countries have similar authorities. They are official documents. Once issued they can only be revoked by the issuing authority.

As the 'College of Arms states, right on their landing page:

"Coats of arms belong to specific individuals and families and there is no such thing as a coat of arms for a family name. From their origins in the twelfth century to the present day arms have been borne by individuals, and by corporate bodies, as marks of identification. They have also been used to denote other characteristics, which have changed over the centuries as society and culture have evolved. New coats of arms have since the fifteenth century been granted both to individuals and corporate bodies by the senior heralds in Royal service, the Kings of Arms" .

Heralds, men like William Camden, possessed the knowledge and resources to issue the coats of arms and are important both to King and country. Heralds are given special authority and protection from harm in life as well as in battle. This is a non-trivial matter. Even today in England, there no more than about 40,000 individuals who are authorized to be the primary bearers of arms. Also, heraldic representation is expressed in specific language that is unique to heraldry and uses arcane, ancient nomenclature that only heralds, and a few others fully understand. It has been standardized since about the 17th century, but had been more or less established since the 13th*, for example: See: The Basic Tinctures. It is possible for a coat of arms to become extinct when the bearer dies with no direct male successor. At that point, it is no longer borne by anyone, not even other relatives unless the bearer willed it.

"At first, armorial bearings were probably like surnames, assumed by each warrior at his free will and pleasure; and, as his object would be to distinguish himself and his followers from others, his cognizance would be respected by the rest, either out of an innate courtesy or a feeling of natural justice disposing men to recognize the right of first occupation, or really from a positive sense of the inconvenience of being identified or confounded with those to whom no common tie united them. Where, however, remoteness of stations kept soldiers aloof, and extensive boundaries, and different classes of enemies from without, subdivided the force of a kingdom into many distinct bands and armies, opportunities of comparing and ascertaining what ensigns had been already appropriated would be lost, and it well might happen, even in the same country, that various families might be found unconsciously using the same arms". (Burke, 1884, pg vi)

To guard against this type of error, the individual's application for a coat of arms must be awarded by the authority. By the time of the reign of Henry V (16 September 1386 – 31 August 1422), the requirement to demonstrate a 'valid right' to bear arms was established. The application goes through a rigourous vetting process both to verify the individual's eligibility based on a set of criteria and to check the artistic representation has not been used by someone else or might present a point of confusion by appearing similar. It is not easy and costs a lot of money. This has been the case since about the early 16th century, just about the time George got his arms: (See Burke's, General Armory, 1884 in the preface, pg vii)

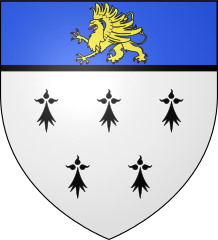

The Coat of Arms granted to George Gynn of Stevenage, Hertfordshire (described above) as an "azure shield with a gold griffin segreant, on a chief indented ermine three pellets" was awarded to one George Gynn, merchant tailor, London and may have looked similar to this:  or possibly this:

or possibly this:

George was born, during the reign of King Henry VIII, but we don't know the exact year. By the time George's 'Coat of Arms' was awarded, during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I (7 September 1533 – 24 March 1603), heraldry was well established both as an art and as a science. Therefore, the likelihood of simply scooping someone else's shield was very unlikely. It follows, by inference, that this coat represents something about George's past. Now today, as Michael Taylor states, there are no modern descendants from this man as his line died out, so this 'Coat of Arms' cannot be used by anyone. But, why would George, a relatively obscure Hertfordshire man (or family) be awarded a 'Coat of Arms'? Was old George telling us something or did he simply borrow the motif?

The description here is in 'The general armory of England, Scotland, Ireland, and Wales by Sir Bernard Burke, 1884, as follows:

(Burke, 1884, pg 437)

(Burke, 1884, pg 437)

In Papworth, this description is altered to read: "... Roundles Az. a griffin segreant or on a chief indented erm. three pellets. Gynn, co. Herts, V.", pg 985

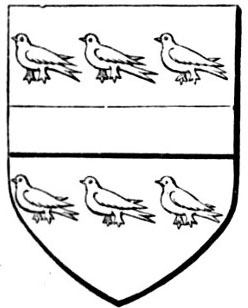

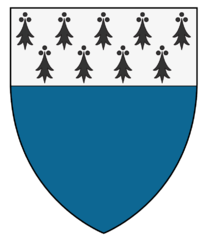

'Gyney' Coats of Arms in Parish Church of St Nicholas (Brandiston, Norfolk)

Several 'Gyney' Coats of Arms once were presented in stained glass lights in Norfolk: Brandiston, Parish Church of St Nicholas. In these 'lights', the 'chief ermine', 'martlets' (small birds) as well as the colour 'Azure' appear. This particular representation may not be the one George conferred on to create his shield but if not, it was likely something similar to this. The 'lights' have long since been removed. They were described as follows:

"Antiquarian accounts provide details of lost glass in four windows of the church. In the original north window of the chancel was a series of heraldic shields. The most complete lists are those in the Harleian and Lansdowne manuscripts which give six coats:

"The church is dedicated to St Nicholas and it was quite common for the dedication of a church not relating to the Holy Trinity, its members, or the Virgin to be marked in a side chancel window. The first and third shields are assigned in the Norfolk and Suffolk Roll of c.1400 to the family of Gyney, patrons of the church from at least 1338 until the mid-fifteenth century; number one is specifically allocated elsewhere to Sir Roger Gyney, who died in 1376, but also to the Gyneys of Gislingham, Suffolk, to whom number three is also given. Number three is assigned to Thomas Gyney in the Norfolk and Suffolk Roll. A Sir Thomas Gyney was the husband of Elizabeth, daughter of Sir Nicholas Bourne, dead by 1366, which explains the presence of number four, given to Sir Nicholas in c.1360, but the Sir Thomas Gyney who was the son of Sir Roger Gyney married Elizabeth, daughter of Sir Thomas Mortimer; her will was proved in 1378. Shield number four is presumably for another member of the Gyney family and the last is unidentified. It is difficult to reconcile the various possibilities of patronage for this window, but the most probable is perhaps that it was intended as a memorial to Sir Roger, the most illustrious member of the family after his death in 1376, with perhaps also a commemoration of Elizabeth, daughter of Sir Nicholas Bourne, who had married into the family".

- Paly of six or and gules a chief ermine, for Gyney.

- Argent a chevron gules between three lions rampant sable, for Bourne.

- Azur an escutcheon and an orle of martlets or, for Gyney.

- Gules an escutcheon and an orle of martlets argent, for Gyney?

- Azure an escutcheon and an orle of martlets argent, for Gyney?

- Azure three leafy branches in point or. Unidentified"

source: https://www.cvma.ac.uk/publications/digital/norfolk/sites/brandiston/history.html

See also: Description of Gyney Arms in A Dictionary of Suffolk Arms by Joan Corder, pg 232 (txt)

The only image of the arms found that answer to the description 'Paly or and gules a chief ermine' are found in this entry:

(A History of the County of Rutland: Volume 2; https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/rutland/vol2/pp265-268)

See also: More about Gyney

While the Gyney family claims descendency from the 'de Guines', so too does the 'Croke' family of Studley, anciently Blount and the shield of the Crokes contains six martlets, thus, against a red background:

Described as: Gules, a fess between six martlets argent.

According to Fairbairn (vol 2, plate 93, # 3, pg 272), the description of the Gynn crest above ( on a garb or, a bird close az.) might have looked like this:

For comparison, here is the 'Jenney' family crest, described as 'on a glove in fesse argent, a hawk or, belled of the last'. (Fairbairn, vol 2, plate 86, # 12, pg 286)

More 'blason's' with similar motifs:

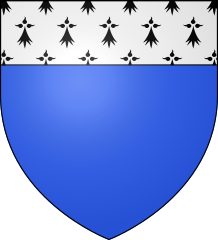

For comparison, here is the 'blason' for 'Pays de Saint-Brieuc (pays historique)'

|

and for the commune of Saint-Brieuc in the département of 'Côtes-d'Armor'  Saint-Brieuc is named after a Welsh monk Brioc, who Christianised the region in the 6th century and established an oratory there. Saint Brioc died in 502. (Wikipedia) |

Blason du Morbihan (Duchy of Brittany) described as: "Coupé ondé d'hermine et d'azur". This design appears closer to the 'wavy' motif. |

Blason de Côtes-d'Armor (Duchy of Brittany) [ Note how colours are reversed but this design is using the 'indented' motif. (French: denté)] |

Armorial des villes de Bretagne

- Village de Gennes-sur-Seiche: Carte de France | Wikipedia

Gennes-sur-Seiche est un petit village du nord ouest de la France. Le village est situé dans le département de l'Ille-et-Vilaine en région Bretagne. Le village de Gennes-sur-Seiche appartient à l'arrondissement de Rennes et au canton d'Argentré-du-Plessis. Le code postal du village de Gennes-sur-Seiche est le 35370 et son code Insee est le 35119. Les habitants de Gennes-sur-Seiche se nomment les Gennois et les Gennoises. In 'Gallo' was simply known as 'Genn'. Note that the pronunciation is with a soft 'G'. - Other villages with a similar name: Gennes (Wikipedia: Disambiguation)

Similar elements are also present in the Arms of Famille Thomasset, Sr de

la Trévillière,

originaire du Poitou:

Described as: 'D'argent à cinq hermines de sable, au chef d'azur chargé d'un griffon passant'.

Armorial des familles de Bretagne

Other similar designs

Emperor of Trébizonde (#1486) (Folio 105) uses alternating ermine and azure bands.

Guillaume, Lord of Broeckhuysen (#1181) along with Henri de Wickerode (# 1191) (folio 89) use a green shield with the 'un chief ermine' motif.

Jean v.d. Donck (# 1214) and Beke (#1218) (folio 90) also display green shields with the 'un chief ermine' motif.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gelre_Armorial

see the original artwork: viewer: https://uurl.kbr.be/1733715

Départements Français - Blasons

- Armorial des communes des Côtes-d'Armor

- Armorial des communes de Finistère

- Armorial des communes d'Ille-et-Vilaine

- Armorial des communes de Loire-Atlantique

- Armorial des communes du Morbihan

This similarity doesn't end here. The arms issued to 'Gynn' in Hertfordshire uses a similar motif (azure, a chief ermine) as 'Lichtervelde (Municipality, Province of West Flanders, Belgium)'. This 'blason' is still used to this day.

The coat of arms, again still used by the Lichtervelde family, is

indeed shown with a chief ermine, that is a non-defined number of ermine spots. (See also: Famille de Lichtervelde)

(source: http://www.francegenweb.org/heraldique//base/details.php?image_id=4000

(source: http://www.francegenweb.org/heraldique//base/details.php?image_id=4000

This Flemish Nobility page discusses the names: Gand, Ghent, Lichtervelde, Mortagne, Wingene and Wijnen.

A similar motif is born by the commune of Ligny-Thilloy in Pas-de-Calais region of France, not far from modern day Belgium:

Described as: 'd'azur au chevron d'hermine'.

About the Lichtervelde coat

The Gelre Armorial refers to a Louis de Lichtervelde, Lord of Coolscamp (#967):

and also a Jean II de Gand, Vilain (#969) (Folio 81) on the same page:

Louis's shield includes a bird but this one is an eagle and not 'close'.

source: http://wappenwiki.org/index.php/Gelre_Armorial_Folio_81

Also found is Roger, Lord of Lichtervelde (#948) (Folio 80) with arms identical to the Lichtervelde family, above:

and a similar design is used by 'Gérard de Halluin, Lord of Lichtervelde' (#990) (Folio 82):

Coincidentally, the 'three lions rampant' motif appears quite similar to the design used by the family 'Lucy' and also by 'William le Genne' (The Lion Rampant in Arms and Heraldry)

source: http://wappenwiki.org/index.php/Gelre_Armorial_Folio_82

Discussion

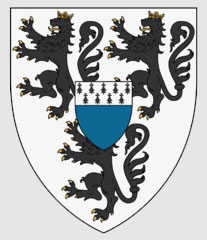

This is a perplexing coincidence of design between the coat awarded to 'Gynn' in Hertfordshire as compared to the coats of arms representing 'Gyney' of Norfolk. So—besides the coat of arms itself, what is the link?

And then there is a second coincidence where 'William le Genne' appears bearing arms that are quite similar to those displayed by 'Gérard de Halluin, Lord of Lichtervelde'. Discussed separately in The Lion Rampant in Arms and Heraldry.

So, why would these coats have elements that resemble another family shield (or an ancient village, or perhaps a noble Flemish family's coat, that of Halluin of Lichtervelde, a well known family and/or place) that - again - most likely had borne these arms from ancient times?

Here's the problem: How can the arms of two men with similar names (Gynn or le Genne) each use components of coats of arms that are in locations, and possibly times, quite far apart?

Further to this, out of hundreds of designs, there are less than a dozen or so that use these similar motifs, so it is fairly obscure and unlikely that a herald would simply run across it in his travels, unless he actually went to Brittany or Lichtervelde in Flanders.

It is quite a surprise to find these similarities, so what does it tell us?

- It could be a simple co-incidence

- It could be 'borrowed'

- It could be a relationship.

IF it is a co-incidence, then the heralds who designed each shield have simply taken design elements and put them together in a similar way. The coats were not designed by the same herald. Each herald would have known about the design elements (azure, a chief ermine) which in itself is not very surprising. What is surprising is that these design elements in each case were combined in almost exactly the same way.

Or, if it is borrowed, then the herald who designed the 'Gynn' coat may have pulled elements from the 'Gyney' or other similar coats, as templates and adapted them. He would have needed to know about the other coat to do this. So, how would he know? And, would it not be a fairly bold move to 'borrow' someone else's arms especially, a family with so similar a name?

Keep in mind that by the early 16th century, the requirement to prove one's right to bear a 'Coat of Arms' was already in place. The bearers of arms, in those days, would have been known to each other - many related - and would guard their honour closely, so simply copying probably would not sit too well, when discovered. So, George would - most likely - have been required to demonstrate this right. Take the case of 'Scrope v Grosvenor' as an example. And someone who bears a coat of arms is not likely simply to lend it since this becomes a permanent representation of a person, or family. Like a modern corporate logo. Also, the knights or other who would have borne the arms would never have been all in the same place at the same time, so in order for the herald to see the shield with the exact design would have taken a bit of work.

In any case, the arms were not simply taken, they must have been awarded by the High Court of Chivalry or whatever preceded it. As mentioned earlier, there is this rigourous vetting process that is part of the application. Today, official approval must be signed off by the Queen herself, but back in the day, the herald held the authority to sign the award.

So, is there a relationship? It would be a stretch to say there is a relationship with any certainty and there is no evidence to show one. But, these heraldic representations are not simply pulled out of thin air.

Michael Taylor says, in his post on this topic: "It is of little use in the sense that no Ginn today (being not descended from George) can strictly actually use the arms, but it has some general interest to the family".

So, we know that George's 'Coat of Arms' cannot represent anyone after his own line died out, however, it is not inconceivable that George is still inadvertently passing along valuable information about his heritage in the form of a graphic representation. Information that cannot be gleaned from the 'life event (B-M-D)/census tract' style of genealogy. The close resemblance of George's coat to other 'blasons' from northern France may be another clue that the 'Gyn' name came from there.

The 'Gyney' coats of arms were presented in the parish church of St Nicholas in Brandiston in Norfolk, very near to the 'de Guînes' family seat in Haverland (now Haveringland). Is it coincidental that the most number of occurrences of the name 'Gyn' or 'Gynn' are in Norfolk and also occur close by in places like Hindolveston, Aylesham, Kirkeby Bidoun, Rougham and Worstead. Note that Blakeney, Geyton Thorpe and Paston are close by as is Stanhoe; Hedenham is a little south and east of Kirkeby Bidoun and Flordon is a little to the southwest. Southery is a bit more to the west. The Gyney family was active in Essex as well, in places such as Steeple Bumsted as well as Great Bardefeld and Little Bardefeld, very close to Hertfordshire. (See Beginnings of the Ginn name or see Norfolk on 'Compare: Gyn/Gynes/Gyney Background Files in East of England (Before 1500)' for location references)

There appears to be a fairly strong correlation here but no clear link or relationship has been found. Further research is needed to either prove, or disprove this assertion, if this is even possible, and also to decipher the message in the shield.

We probably will never know the connections but perhaps old George did know. Again, might he have borrowed the motif in the coat of arms of 'Gyney' or is there a relationship?

Even if we discover a connection to the 'Gyney' coat of arms, there are other issues that remain to be resolved. Specifically, what is the connection between 'Gyney' in Norfolk and our people in Hertfordshire. These important details will likely remain unknown because the records that might reveal the information we need to close these gaps don't exist. Still, it is a compelling mystery.

Notes

Note that the Belgian shields (aka blasons) generally use 'lions rampant' as their animal motif (a real animal) whereas the the 'Gynn' coat of arms used a gold gryphon - a mystical creature. The 'griffin' often appears in French heraldry, in Bretagne and other parts in the north. Heraldic griffins can take many forms. (Wikipedia) Griffins also appear in heraldic representations in other countries, especially Germany, Poland and Sweden.

Also note that none of the 'Lichtervelde' shields use the indented motif whereas the 'Côtes-d'Armor' and 'Morbihan' ones have adopted a similar design element. This may indicate that there is no connection between these places.

A gold gryphon against a blue shield also appears on the coat for a Read family in Ireland. See: Read (Dunboyne Co. Meath, Ireland) coat of arms. This is very similar to the coat for Boissel. Note the similarity to the blason for Saint-Brieuc.

There is no known connection to any of these arms or between any of these people.

Ermine represents wealth and power

As the above picture shows the 'Duke of Brittany' in plain ermine, a few words about this motif are called for.

"The coat of arms of Brittany, ermine plain, was adopted by John III in 1316. Ermine had been used in Brittany long before, and there is no clue about its origin. It was probably chosen by the dukes because of its similarity with the French fleur-de-lis". (Wikipedia)

Another illustration of the 'Duc de Bretaigne' in his tournament dress. Armorial de l'Europe et de la Toison d'or; Publication date: 1401-1500

(source: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b55009806h/f145.item.zoom)For a complete overview see: Bretagne by Hubert de Vries.

Ermine (heraldry)

"[T]he association of the ermine fur with the linings of coronation cloaks, crowns and peerage caps, the heraldic tincture of ermine was usually reserved to similar applications in heraldry (i.e., the linings of crowns and chapeaux and of the royal canopy)."

"It is the fur most commonly used in heraldry, and the spots represent the tails of this small animal, sewn to the white fur for enrichment. This is a regal fur, since ermine has long been associated with the crowns and robes of royal and noble persons. It symbolizes valor, justice and dignity. (Furs of Heraldry - Knowledge Base, HouseofNames.com) "

source: https://www.houseofnames.com

Ermine is relatively rare in heraldry: See: Historical trends in the deployment of tinctures by Prof. G.R. Sampson, Table A. (Used in 9 out of medieval 384 samples or 2.3%) ... Azure is also relatively uncommon, as the other tables on this page demonstrate.

*As Patrick Baty says: "Volume 3 (of the Dictionary of Colours for Interior Decoration, v 3) tells us that:

"These heraldic terms date from the early thirteenth century, when heraldry became established as a science. The heraldic colour names are mainly of French derivation, or influenced by Latin. The names are still used in heraldry today".

Royal Ermine

Sable might be today's uncontested king of luxury furs, but historically, ermine was the status quo fur for royalty, and the most sought-after fur for court presentations and official portraiture. ... White ermine with its trademark black tail-tip became so entrenched with aristocratic fashion from the medieval period onwards that it even found a place in heraldry. For example, the coat of arms of Bretagne (Brittany), in France, references ermine markings in its design.

"Heraldry in its origin and purpose was a visual art. Its main tinctures or colours were gules or red, symbol of martial fortitude and magnanimity; azure or blue, symbol of loyalty and truth; sable or black, symbol of constancy and grief; vert or green, symbol of hope and joy and purpose or purple, symbol of royalty and justice. The chief metals used were or (gold), depicted as a bright yellow, symbolising generosity and elevation of mind, and argent (silver) depicted as white indicating peace of sincerity. The furs of heraldry signify a mark of dignity, in addition to the symbolism attached to their various colours. The furs are: ermine, ermines, erminois, pean, vair, countervair, potent and counter-potent. Simple coats of arms are usually the most ancient, often consisting of a single division of the shield into two colours or one colour and a metal". (The Origins of Heraldry by J. D. Williams, Clare County Library)

The Symbolism of Purity in the Christmas Scene by Marian Therese Horvat, Ph.D.

"A white field with black spots - the spots representing the black tipped tails of these small animals - also appeared on the coats of arms of knights as a sign that they would prefer death rather than to stain their honor and conscience. ...

Legend has it that hunters seeking the highly prized fur of the small animal would smear the entrance of its lair with mud, then begin the hunt. Tired and exhausted after a long chase, the ermine would flee to its home, only to find the mud on the entranceway. Rather than sully its coats by running through the filth, the ermine would give itself up to the hunters and dogs who had followed it. Thus the ermine became associated with phrases such as Death before Defilement, and Death rather than Dishonor. ...

Obviously, the purity, innocence, and nobility of the ermine is symbolized in its highest degree in the Christ Child, the most pure and noble of all beings. There is another layer to the symbolism: because the ermine's coat turns brown in the summer, the ermine seems to die and then be reborn in the winter. Therefore it also stand's for Christ's Resurrection".

More about Lichtervelde: (Note: Again, there is no known connection but is included here because of the similarity of design motif.)

| Van Lichtervelde | Azure, a chief Ermine, the shield accompanied of a bordure engrailed Gules. Supporters: two stags, Proper. |

| Van Lichtervelde | Azure, a chief Ermine. Crest: two horn of buffalo Or. Or : Crowned Helmet. Crest: a head and neck of swan Argent, beaked Gules between a couped vol of 2 wings conjoined in base alternatively Vert and Argent. Supporters: two stags, Proper. |

| Van Lichtervelde | Azure, a chief Ermine, charged of a dove Argent, wide vol of 2 wings conjoined in base. Crest: a dove, closed vol of 2 wings conjoined in base. |

source: http://www.coats-of-arms-heraldry.com/armoriaux/rietstap/blasons_LIAN_LIEC.html

One 'Agnès de LICHTERVELDE' married 'Roger van WINGENE' (Note: Wingene (West Flemish: Wijnen) is the Dutch name for the village of Guines in Pas-de-Calais)

https://gw.geneanet.org/ageorgery2?lang=en&pz=nicolas&nz=georgery&p=agnes&n=de+lichtervelde

see also: The Dudzeele and Straten Ancestry of Catherine de Baillon, Part 1 by John P. DuLong (https://habitant.org/articles/DuLong,%20The%20Dudzeele%20and%20Straten%20Ancestry%20of%20Catherine%20de%20Baillon,%20Both%20Parts%20(2011).pdf) pg 22